On a crisp, clear, autumn day in the Smoky Mountain town of Sapphire, N.C., Attorney General Roy Cooper was thinking about the many days when air pollution blankets his state's scenic views in haze and sends its citizens to hospitals, gasping for breath.

"It's a beautiful day in the North Carolina Mountains. But that quality of life is being threatened by pollution that's coming across the state line," Cooper said. "Anyone who has been in the Smoky Mountains on an incredible day like today know[s] that haze should not be a part of the Smoky Mountains."

On this day, the air was so clear that visitors could make out the nooks and crannies of a rock outcropping on a nearby mountain. But on many days in the summer, the haze is so thick in North Carolina's mountains that instead of seeing ridge after ridge for 100 miles, visitors can barely make out the closest mountains.

Cooper tried conventional means to stop out-of-state pollution from fouling the state's air. He asked the Environmental Protection Agency to use the Clean Air Act to force upwind coal-fired power plants to slash emissions. But the EPA denied the state's petition.

So Cooper resorted to a different strategy. He sued the company he considers the biggest single offender, the Tennessee Valley Authority, a federal utility that owns all the coal-fired power plants in Tennessee and several more in Kentucky and Alabama.

"We know that air pollution from the Tennessee Valley Authority is making people sick. It's causing haze across our mountains, it's killing our trees, it's polluting our waters. We want it to stop. We've asked them nicely. We've tried to work with them. They've not responded," Cooper said. "Litigation is the last resort."

Dusting Off an Old Legal Tool

Cooper felt that modern pollution laws were not making North Carolina's air clear and healthy quickly enough, so he turned to the same legal tool that property owners have used through the ages to settle disputes with neighbors, a public nuisance suit.

"When you have people being forced to go to the hospital; when you have little children with asthma who can't go outside on particularly hot, stuffy days; when seniors can't take a walk because of breathing problems; when tourism dollars are being lost; that's clearly a public nuisance under the law," Cooper said.

Cooper's suit triggered a war of words and statistics between himself and Bill Baxter, who sits on TVA's board of directors.

"TVA is very easy to pick on. It's a big organization with a big target on its back," Baxter said. "The facts are that we are spending billions of dollars of our ratepayers' money and we're getting huge reductions in our emissions. We're proud of the progress we've made. But we're not done yet. And we're going to keep on."

Baxter said it is ridiculous for Cooper to argue that TVA's contributions to North Carolina's bad air constitute a public nuisance, because there are so many other sources of pollution.

"Well, under that theory, he ought to sue every automobile owner in his own state, every owner of a lawn tractor and everyone who has a power plant in North Carolina. But you know that's not good politics," Baxter said.

In fact, the biggest source of dirty air in North Carolina is its own power plants; the state legislature passed a law to require them to slash pollution by two-thirds over the next several years.

TVA's Efforts to Clean Up

Baxter argues that over the years, the TVA has done far more than utilities in North Carolina to improve air quality.

"We have now reduced our emissions from our coal-fired plants by 80 percent," he said. "We've spent $4.4 billion doing that," Baxter said.

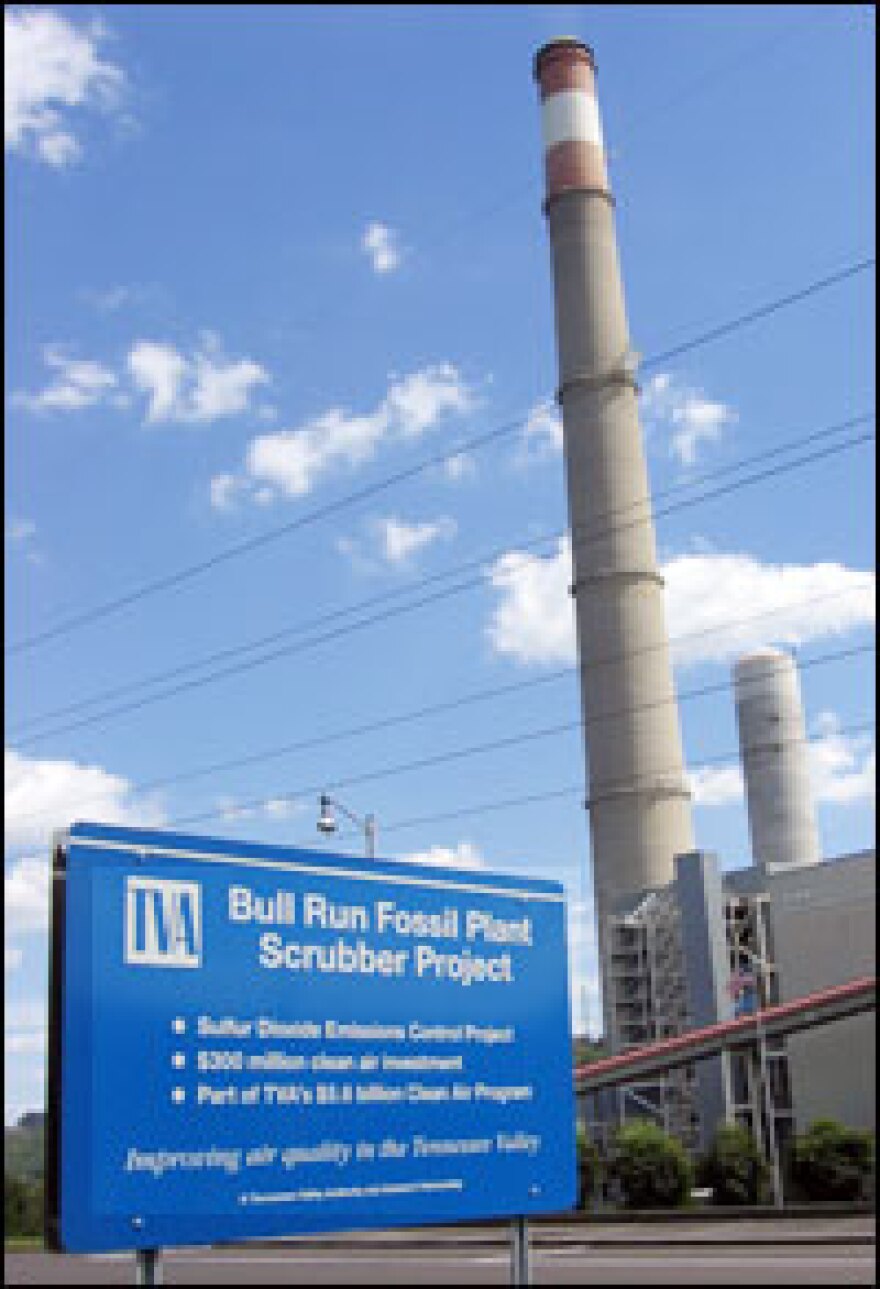

To underscore that point, TVA officials pointed to Bull Run, one of the largest of TVA's 11 coal-fired power plants. The plant was built in the 1960s, before advanced pollution controls were required. But in the last few years, TVA installed modern pollution-control equipment to reduce emissions of nitrogen oxides, which cause smog. And it currently is constructing a scrubber, which strips 95 percent of the plant's emissions of sulfur dioxide, the pollutant most responsible for the haze that obscures views.

Despite all these efforts, TVA remains one of the largest emitters of air pollution in the country. Only one-third of the electricity it produces from coal is from power plants that have installed scrubbers, the best technology for reducing sulfur dioxide emissions.

"We are a major emitter. We've also had major progress in reductions," Baxter said, adding, "We're in compliance with every part of the Clean Air Act."

But that was not what EPA officials thought. During both the Clinton and Bush administrations. they found that the TVA had violated the Clean Air Act by failing to install modern pollution controls when the company made major renovations or repairs at nine of its plants and increased emissions. TVA has fought those charges in court, and has used its special status as a federal corporation to prevent the agency from requiring changes.

Waiting for Clean Air

Baxter and EPA officials said that current regulations will force enough cleanup of power plants in the coming decade to make North Carolina healthy.

But Cooper said the federal rules adopted by the Bush administration will not clean up the air fast enough.

"We don't want to wait another generation for clean air here in the North Carolina mountains," Cooper said.

He wants TVA to agree to cut emissions as much as North Carolina's plants have to under the state's "clean smokestack" law.

"If they would do that, this lawsuit goes away." Cooper said. "But the problem is they don't want to enter into any legally binding, enforceable agreements with North Carolina or anybody else."

Health Consequences

The attorney general is not the only one who is impatient for clean air in North Carolina.

Clay Ballentine is a doctor at the biggest hospital in the western part of the state. He said he regularly sees the agony air pollution causes his patients.

"When these people come in here with exacerbations of their emphysema or asthma, it's as if they're smothering," Ballentine said. "They cannot breath. They cannot get adequate air in. Unless they have an effective rescue here in the emergency department or in the hospital, they will die from this."

Recent studies have shown that air pollution is deadly for people who live downwind from coal-fired power plants. Each year, it causes tens of thousands of Americans to die early from lung failure, heart attacks and strokes.

Ballentine says that whenever the air quality is bad, local residents and tourists flock to the hospital.

"When air pollution makes these people smother and come in here gasping literally for their lives, then it's time to get angry about it and do something about it," Ballentine said.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.