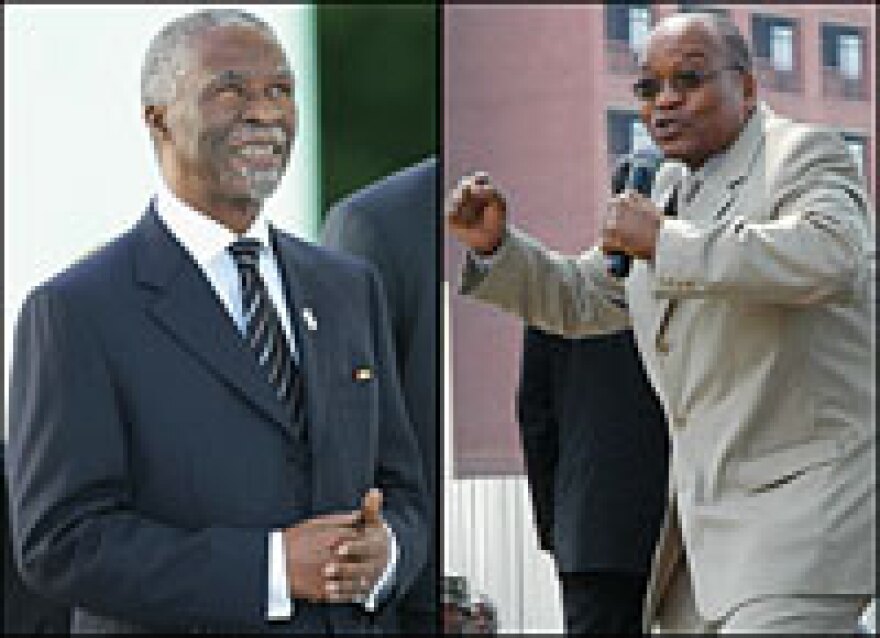

The election of Jacob Zuma as president of the African National Congress marks the end of one phase of a fierce power struggle.

During this time, veterans of the fight against apartheid vied for control of the party — and of the South African government. But after the vote, Zuma and his rival, South African President Thabo Mbeki, made a strong show of unity.

They sought to calm what has been an unsettling time for many South Africans, who are used to solidarity from the organization that led black resistance to the country's white-minority government throughout much of the 20th century.

The ANC was formed in 1912, just two years after Britain had granted independence to its former colony and placed its government in the hands of the small white population. The white South Africans were Afrikaners, the descendents of Dutch settlers, and British immigrants, many of whom had come to exploit the country's gold and diamond resources.

South Africa's white-owned farms and mines needed labor, and the government passed a series of laws and taxes designed to force black people off their own land and into the labor market. Most of the workers were migrants, men who lived most of the year in barracks at the mines and farms — and returned only briefly to their families in rural areas. The movements of black workers were strictly controlled by a pass system, which limited where they could go.

The ANC led protests against the pass laws in 1919 and supported a strike by black mineworkers in 1920, but its leadership generally favored a more persuasive, less militant approach. During much of the decade, the ANC was less active than the black trade unions and the Communist Party.

The ANC gained strength in the 1940s, as more black South Africans migrated to the cities to work in war-time factories and industries. Women, who were allowed only affiliate membership in the 1930s, gained full membership in 1943.

In 1944, young African nationalists in the party formed the ANC Youth League, which sought to organize militant resistance against race-based laws that were becoming increasingly restrictive toward blacks. The youth leaders included Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Oliver Tambo, who advocated strikes, boycotts and protests to counter the white government's policy of racial separation, known as apartheid.

In 1956, the government arrested more than 150 leaders of the ANC and allied organizations. They were tried for treason and finally acquitted five years later.

In 1960, the South African government expanded the pass laws, which required blacks to carry identity passes to show they had permission to enter white areas. An ANC splinter group organized an unarmed protest against the laws, which extended the pass requirements to women, many of whom worked as domestic servants in white neighborhoods. Police fired on the demonstrators, killing nearly 70 in what came to be known as the Sharpeville Massacre.

After the massacre, the South African government banned both ANC and the splinter group, known as the Pan Africanist Congress, from political activity. Members of the ANC's military wing, including Mandela, were arrested and sent to a political prison on Robben Island, off the South African coast. With funding from the former Soviet Union, exiled ANC members formed militant cells in neighboring countries, staging bombings and armed attacks across the border. The United States and other Western governments joined with the South African government in declaring the ANC to be a terrorist group.

International opposition to South Africa's white-minority rule grew over the next three decades, resulting in sanctions and boycotts that put economic pressure on the government. The collapse of the Soviet Union after 1989 cost the ANC much of its funding and forced it to adopt a more conciliatory tone. The two sides held peace talks, and the ban against the ANC was lifted in 1990.

The ANC formed a three-way alliance with the South African Communist Party and the Congress of South African Trade Unions, winning the 1994 general election and making Nelson Mandela the country's first black president. Since then, the ANC has been the majority party in South Africa, holding so much power that whoever leads the party is expected to win the presidency in 2009.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.