“Beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror,” the poet Rainer Marie Rilke writes, “which we are still just able to endure, and we are so awed because it serenely disdains to annihilate us.”

It's a definition that could have been inspired by the beauty of the American West – Trans-Pecos Texas included. Encountering a landscape of soaring mountains and vertiginous vistas, we sense powerful forces beyond our ken or control.

One of those forces is known as the Rio Grande Rift. From Colorado to the Big Bend, the continent is being torn apart. Though it provides the route for its namesake river, the Rift itself is far more ancient. Geologists are still laboring to understand this continent-shaping phenomenon.

Jason Ricketts, a University of Texas-El Paso professor, studies the Rift.

“If you were to stand on the eastern segment of the Rift,” Ricketts said, “and I was to stand on the western edge, and we looked across the Rift at each other for a whole year, then after that year we'd be farther apart – although the distance we'd travel is not that great: it would be about the thickness of a penny.”

Movement today is generally slow – but it can happen rapidly in earthquakes. And in geologic time, the results have been dramatic. The Earth's crust has stretched and broken in faults, raising up mountains – including the Franklins and Guadalupes, the Carmens and the Mesa de Anguila in Big Bend.

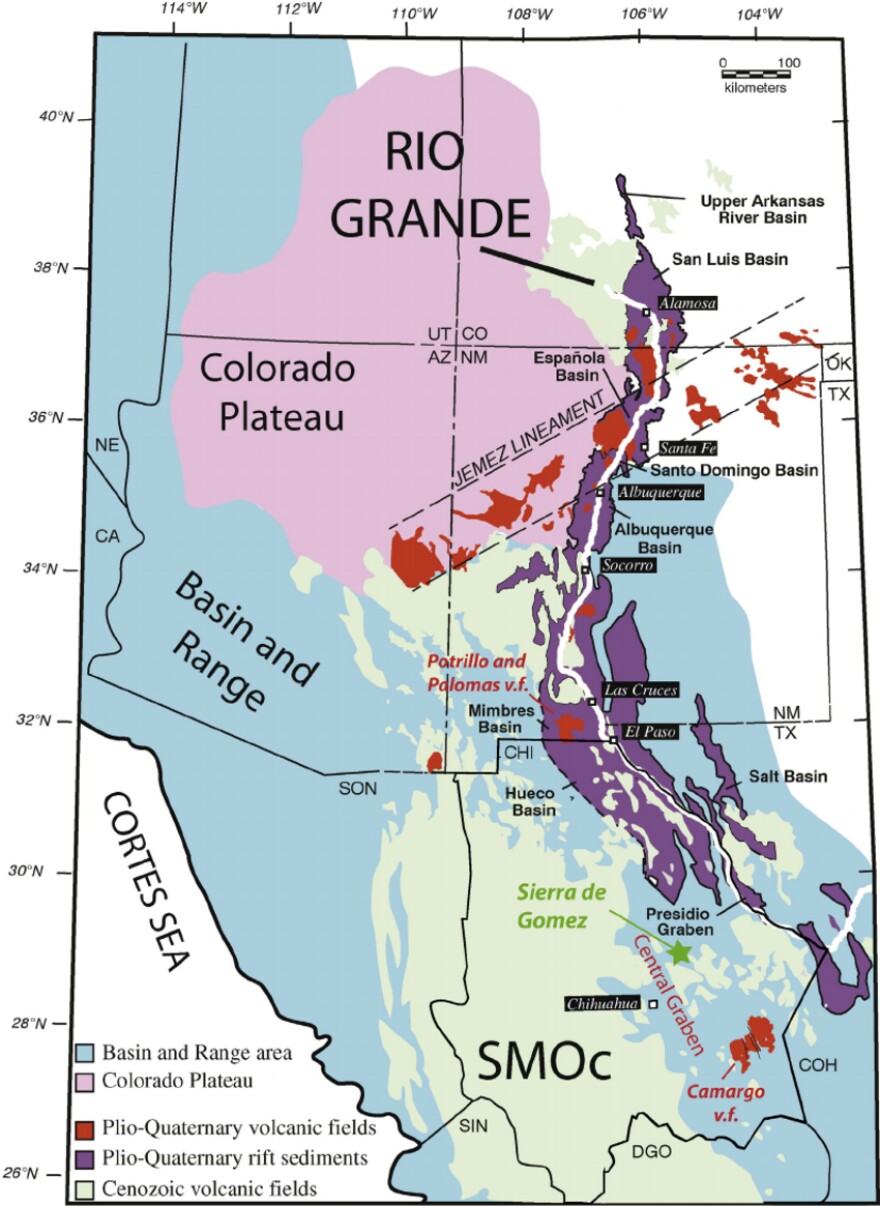

From Colorado to central New Mexico, the Rift creates a series of narrow basins. Farther south, in Texas and Chihuahua, it widens and expands.

What's causing this “tearing”? As vast as the Rift is, it's part of an even larger story, Ricketts said.

“A lot of it is interwoven,” he said. “If you talk about the Rift, it's really not appropriate to close your eyes and discount all the other things happening in western North America. They're all kind of telling the same story, but different parts of it.”

It begins some 165 million years ago, when an oceanic plate, called the Farallon, collided with and then began to slide under North America – in a process called “flat-slab subduction.” As the Farallon Plate worked its way beneath our continent, North America was squished and thickened. Ancient strata were thrust upward – and are exposed today in parts of the Rocky Mountains, and in West Texas.

But about 40 million years ago, the Farallon Plate reached the Great Plains, and began to “founder” – to break apart and sink into the molten abyss of the Earth's mantle. That “foundering” heated our continent at its depths. Powerful volcanism resulted, and the evidence is visible today from the Chisos Mountains to the San Juans in Colorado.

With the compressive force of the Farallon Plate removed, North America began to spread and stretch westward. Western North America was torn and broken – creating alternating valleys and mountains, “basins and ranges,” from New Mexico and Utah to California. The Rio Grande Rift is both part of, and distinct from, that broader “extension.”

Ricketts is using a cutting-edge technique to explore this history. It's called “thermochronology” – and it involves minerals called apatite and zircon.

“Those minerals to me are really amazing – they remember their thermal history,” Ricketts said. “They remember when they cooled to low temperatures. As geologists, if we can ask the rocks and ask those minerals specific questions, and we're very careful about how we collect our samples, then they can tell us a lot about how the Rift formed.”

The two minerals contain uranium and thorium – and as these radioactive elements decay, they release helium. That helium “leaks out” when the minerals are hot. But when apatite and zircon cool, their crystalline structures trap the helium. By analyzing the ratio of helium to the radioactive elements, geologists can date when the minerals cooled – which is when their host rocks were raised up and exposed at the surface by the tectonic forces of the Rift.

Ricketts has found that the Rift was most active at the same time along its entire length.

“And that time frame, when extension was the fastest, was about 25 to 10 million years ago,” he said. “So before that much of the extension was relatively slow, and since 10 million years it's really slowed down as well.”

The Rio Grande Rift is one of two prime examples of active continental rifting. The other – the East African Rift – contains some of the earliest evidence of our species. The Rio Grande Rift has been studied extensively – but geologists still debate why it developed when and where it did.

One theory involves the Colorado Plateau – that region of canyons that spans the “four corners” of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah and Colorado. The Colorado Plateau has remained intact throughout the West's tectonic upheaval – seemingly unaffected by all the squeezing and stretching. Its stability is a mystery. As the West extends, the Colorado Plateau is being pulled and rotated as a unit – and that movement could be ripping the continent apart at the Rift.

Ricketts thinks “mantle processes” are part of the explanation. In its subterranean foundering, the Farallon Plate broke into slabs. Heat rose up where slabs detached, and weakened the Earth's crust. If a giant, 600-mile-wide slab detached beneath the Rift's current location, it would have set the conditions for the “tearing” to occur.

The Rift's most active epoch is past. But its power isn't entirely spent. The Trans-Pecos has seen significant earthquakes during the past century. And it's certain there will be larger earthquakes in the future. One fault runs directly through downtown El Paso and Juarez – a 6- or 7-magnitude quake there could be devastating. Recent research indicates the last such quake hit about 12,000 years ago.

Volcanism, too, is part of the Rift's repertoire – and it isn't all ancient history. The Rift produced the Carrizozo lava flows, in southern New Mexico, only a few thousand years ago.

The Rift not only shapes the landscape – it is, in a real way, the foundation for life here. The Rio Grande is a desert lifeline – we wouldn't have the river without the Rift. And Rift faults determine the location of precious groundwater resources. It's an area Ricketts studies.

“If we can understand how the Rift formed,” he said, “and how the geometry of the faults helps to compartmentalize the water, then we can answer really important questions like – how much water is left, before we pump it all out? Understanding those things is really necessary if we want to continue living in dry areas like this and sustain large populations.”

If you're a Trans-Pecos resident, there are many ways to describe your home: as part of Texas, the borderlands or the Chihuahuan Desert. Add the Rio Grande Rift to that list – in a sense, it's the most fundamental address you can give.